2 The Nix Package Manager

2.1 Introduction

Nix is a package manager that can be installed on your computer, regardless of the operating system. If you are familiar with the Ubuntu Linux distribution, you have likely used apt-get to install software. On macOS, you may have used homebrew for similar purposes. Nix functions in a comparable way but has many advantages over classic package managers, as it focuses on reproducible builds and downloads packages from nixpkgs, currently the largest software repository1.

In this chapter, we will explore the critical need for environment reproducibility in modern workflows. We will see why ad-hoc tools often fail, and how Nix’s declarative approach and “component closures” provide a robust solution. We will also cover the core concepts of Nix—derivations, the store, and hermetic builds—that make this possible.

2.2 Why Reproducibility? Why Nix?

2.2.1 Motivation: Reproducibility in Scientific and Data Workflows

To ensure that a project is reproducible you need to deal with at least four things:

- Ensure the required version of your programming language (R, Python, etc.) is installed.

- Ensure the required versions of all packages are installed.

- Ensure all necessary system dependencies are installed (for example, a working Java installation for the

{rJava}R package on Linux). - Ensure you can install all of this on the hardware you have on hand.

But in practice, one or most of these bullet points are missing from projects. The goal of this course is to learn how to fulfil all the requirements to build reproducible projects.

The current consensus for tackling the first three points is often a mixture of tools: Docker for system dependencies, {renv} or uv for package management, and tools like the R installation manager (rig) for language versions. As for the last point, hardware architecture, the only way out is to be able to compile the software for the target platform. This involves a lot of moving parts and requires significant knowledge to get right.

2.2.2 Problems with Ad-Hoc Tools

Tools like Python’s venv or R’s renv only deal with some pieces of the reproducibility puzzle. Often, they assume an underlying OS, do not capture system-level dependencies (like libxml2, pandoc, or curl), and require users to “rebuild” their environments from partial metadata. Docker helps but introduces overhead, security challenges, and complexity, and just adding it to your project doesn’t make it reproducible if you don’t explicitly take some precautionary steps.

Traditional approaches fail to capture the entire dependency graph of a project in a deterministic way. This leads to “it works on my machine” syndromes, onboarding delays, and subtle bugs.

2.2.3 Nix: A Declarative Solution

With Nix, we can handle all of these challenges with a single tool.

The first advantage of Nix is that its repository, nixpkgs, is humongous. As of this writing, it contains over 120,000 pieces of software, including the entirety of CRAN and Bioconductor. This means you can use Nix to handle everything: R, Python, Julia, their respective packages, and any other software available through nixpkgs, making it particularly useful for polyglot pipelines.

The second and most crucial advantage is that Nix allows you to install software in (relatively) isolated environments. When you start a new project, you can use Nix to install a project-specific version of R and all its packages. These dependencies are used only for that project. If you switch to another project, you switch to a different, independent environment. But this also means that all the dependencies of R and R packages, plus all of their dependencies and so on get installed as well. Your project’s development environment will not depend on anything outside of it (well, there are some caveats which we will explore as we move on).

This is similar to {renv}, but the difference is profound: you get not only a project-specific library of R packages but also a project-specific R version and all the necessary system dependencies. For example, if you need {xlsx}, Nix automatically figures out that Java is required and installs and configures it for you, without any intervention.

What’s more, you can pin your project to a specific revision of the nixpkgs repository. This ensures that every package Nix installs will always be at the exact same version, regardless of when or where the project is built. The environment is defined in a simple plain-text file, and anyone using that file will get a byte-for-byte identical environment, even on a different operating system.

2.3 Important Concepts

Before we start using Nix, it is important to spend some time learning about some Nix-centric concepts, starting with the derivation.

In Nix terminology, a derivation is a specification for running an executable on precisely defined input files to repeatably produce output files at uniquely determined file system paths. (source)

In simpler terms, a derivation is a recipe with precisely defined inputs, steps, and a fixed output. This means that given identical inputs and build steps, the exact same output will always be produced. To achieve this level of reproducibility, several important measures must be taken:

- All inputs to a derivation must be explicitly declared (and “inputs” here is meant in a very broad sense; for example, configuration flags are also inputs!).

- Inputs include not just data files but also software dependencies, configuration flags, and environment variables: essentially, anything necessary for the build process.

- The build process takes place in a hermetic sandbox to ensure the exact same output is always produced.

The next sections explain these three points in more detail.

2.3.1 Derivations

Here is an example of a simple Nix expression:

let

pkgs = import (fetchTarball "https://github.com/rstats-on-nix/nixpkgs/archive/2025-04-11.tar.gz") {};

in

pkgs.stdenv.mkDerivation {

name = "filtered_mtcars";

buildInputs = [ pkgs.gawk ];

dontUnpack = true;

src = ./mtcars.csv;

installPhase = ''

mkdir -p $out

awk -F',' 'NR==1 || $9=="1" { print }' $src > $out/filtered.csv

'';

}Without going into too much detail, this code uses awk, a common Unix data processing tool, to filter the mtcars.csv file. As you can see, a significant amount of boilerplate is required for this simple operation. However, this approach is completely reproducible: the dependencies are declared and pinned to a specific version of the nixpkgs repository. The only thing that could make this small pipeline fail is if the mtcars.csv file is not provided to it.

Nix builds the filtered.csv output file in two steps: it first generates a derivation from this expression, and only then does it build the output. For clarity, I will refer to code like the example above as a derivation rather than an expression, to avoid confusion with the concept of an expression in R.

The goal of the tools we will use in this book, {rix} and {rixpress} (or ryxpress if you prefer using Python), is to help you create pipelines from such derivations without needing to learn the Nix language itself, while still benefiting from its powerful reproducibility features.

2.3.2 Dependencies of derivations

Nix requires that the dependencies of any derivation be explicitly listed and managed by Nix itself. If you are building an output that requires Quarto, then Quarto must be explicitly listed as an input, even if you already have it installed on your system. The same applies to Quarto’s dependencies, and their dependencies, all the way down. To run a linear regression with R, you essentially need Nix to build the entire universe of software that R depends on first.

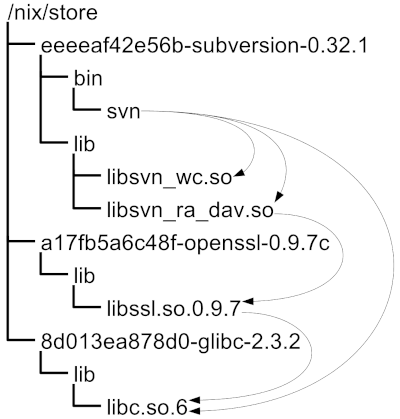

In Nix terms, this complete set of packages is what its author, Eelco Dolstra, refers to as a component closure:

The idea is to always deploy component closures: if we deploy a component, then we must also deploy its dependencies, their dependencies, and so on. That is, we must always deploy a set of components that is closed under the ‘depends on’ relation.

(Nix: A Safe and Policy-Free System for Software Deployment, Dolstra et al., 2004).

In the figure, subversion depends on openssl, which itself depends on glibc. Similarly, if you write a derivation to filter mtcars, it requires an input file, R, {dplyr}, and all of their respective dependencies. All of these must be managed by Nix. If any dependency exists “outside” this closure, the pipeline will only work on your machine, defeating the purpose of reproducibility.

2.3.3 The Nix store and hermetic builds

When building derivations, their outputs are saved into the Nix store. Typically located at /nix/store/, this folder contains all the software and build artefacts produced by Nix.

For example, the output of a derivation might be stored at a path like /nix/store/81k4s9q652jlka0c36khpscnmr8wk7jb-filtered. The long cryptographic hash uniquely identifies the build output and is computed based on the content of the derivation and all its inputs. This ensures that the build is fully reproducible.

As a result, building the same derivation on two different machines will yield the same cryptographic hash. You can substitute the built artefact with the derivation that generates it one-to-one, just as in mathematics, where writing \(f(2)\) is the same as writing \(4\) for the function \(f(x) := x^2\).

To guarantee that derivations always produce identical outputs, builds must occur in an isolated environment known as a hermetic sandbox. This process ensures that the build is unaffected by external factors, such as the state of the host system. This isolation extends to environment variables and even network access. If you need to download data from an API, for example, it will not work from within the build sandbox. This may seem restrictive, but it makes perfect sense for reproducibility: an API’s output can change over time.

For a truly reproducible result, you should obtain the data once, version it, and use that archived data as an input to your analysis.

2.3.4 Other key Nix concepts

We’ve covered derivations, dependencies, closures, the Nix store, and hermetic builds. That’s the core of what makes Nix tick. But there are a few more concepts worth knowing about before we move on:

Purity: Nix tries very hard to keep builds “pure”: the output only depends on what you explicitly list as inputs. If a build script tries to reach out to the internet or read some random file on your machine, Nix will block it. That can feel restrictive at first, but it’s what guarantees reproducibility.

Binary caches: You don’t always need to build everything yourself. Think back to the math analogy: if you already know that \(f(2) = 4\), there’s no need to compute it again; just reuse the result! Nix does the same with binary caches: because every build is identified by its unique cryptographic hash made from its inputs, this means a prebuilt package fetched from

cache.nixos.org(or your own cache you may want to set up) is bit-for-bit identical to what you would have built locally. This is why Nix is both reproducible and fast.Garbage collection: Since Nix never overwrites anything in the store, old packages can pile up. Running

nix-store --gcwill run the garbage collector to free up space.Overlays: If you want to tweak a package or add your own without forking all of

nixpkgs, you can use overlays. They let you extend or override existing definitions in a clean, composable way.Flakes: The newer way to define and pin Nix projects. Flakes make it easier to share and reuse Nix setups across machines and repositories. There is a lot of discussion around flakes, as they’re officially still considered not stable, even though they’ve been widely adopted by the community. But don’t worry, this is not something you’ll need to think about for this book.

Together, these features explain why Nix isn’t just another package manager. It’s more like a framework for reproducible environments that can scale from a single project to an entire operating system (called NixOS2).

As a little sidenote: I want also to highlight that Nix can even be used to declaratively and reproducibly configure your operating system (be it NixOS, macOS or other Linux distributions) using a tool that integrates with it called homemanager.3 This is outside the scope of this book, but I wanted to highlight it, as it’s extremely powerful. What this means in practice is that you could write a whole Nix expression that not only downloads and configures software, but even sets up users with their specific software, and preferences like wallpapers, colour schemes and so on.

2.4 Caveats

While Nix is powerful, there are some limitations and practical hurdles to be aware of if you plan to use it for actual work:

Hardware acceleration: On non-NixOS systems, it can be difficult to set up GPU acceleration (CUDA, ROCm, OpenCL). Drivers are tightly coupled to the host kernel and libraries, while Nix builds aim for strict isolation. On NixOS this integration is smoother, but on macOS or other Linux distros you may encounter limitations or extra manual steps.

macOS-specific issues: Reproducibility is harder to achieve on macOS (both Intel and Apple Silicon) than on Linux. Nix packages often rely on Apple system frameworks (e.g., CoreFoundation, Security) that live outside the Nix store and compromise hermetic builds4. The macOS sandbox is also weaker than Linux’s and sometimes leaks system tools like Xcode or Rosetta into builds5. Hydra cache coverage is thinner for Darwin platforms, especially Apple Silicon, so cache misses and local builds are much more common6. Finally, pinned environments can break after macOS or Xcode updates because of changes in system libraries or compiler flags7.

That said, in practice most packages build fine on macOS, and the ecosystem continues to improve. When reproducibility problems do appear, the simplest fix is often just to use another nearby

nixpkgsrevision for pinning that is known to work. This makes the situation less fragile than it might first appear. Another solution would be to use Docker to deploy the Nix environment and use that as a dev container. All of this will be discussed in detail in this book.Steep learning curve: The Nix language and ecosystem (flakes, overlays, derivations) can be conceptually difficult if you come from traditional package managers. Even basic customizations require some ramp-up time. This was my main motivation to write

{rix},{rixpress}(for R) andryxpress(for Python).Disk space and builds: Because Nix never mutates software in place, the store can accumulate large amounts of data. Cache misses sometimes force local builds, which can be slow and resource-intensive. However, it is of course possible to empty the Nix store to recover disk space, and it is also possible to set up your own project cache if you wish so. Setting up your own cache will also be something that we will explore in this book.

These caveats don’t diminish Nix’s strengths but highlight that its guarantees are strongest on Linux (and thus WSL), and especially on NixOS. On macOS, reproducibility is possible but sometimes requires extra work, a bit of flexibility, and occasionally picking a different nixpkgs snapshot.

2.5 In summary

Nix makes it possible to actually build software reproducibly. To achieve this, it introduces several core concepts that are quite specific, and definitely worth taking the time to understand.

In the next chapter, we will learn how to install Nix, configure cachix, and set up Positron for a seamless development experience.

https://repology.org/repositories/graphs↩︎

https://nixos.org/↩︎

https://github.com/nix-community/home-manager↩︎

https://github.com/NixOS/nixpkgs/issues/67166↩︎

https://discourse.nixos.org/t/nix-macos-sandbox-issues-in-nix-2-4-and-later/17475↩︎

https://www.reddit.com/r/NixOS/comments/17uxj6q/how_does_nix_package_manager_work_on_apple_silicon/↩︎

https://github.com/NixOS/nix/issues/11679↩︎